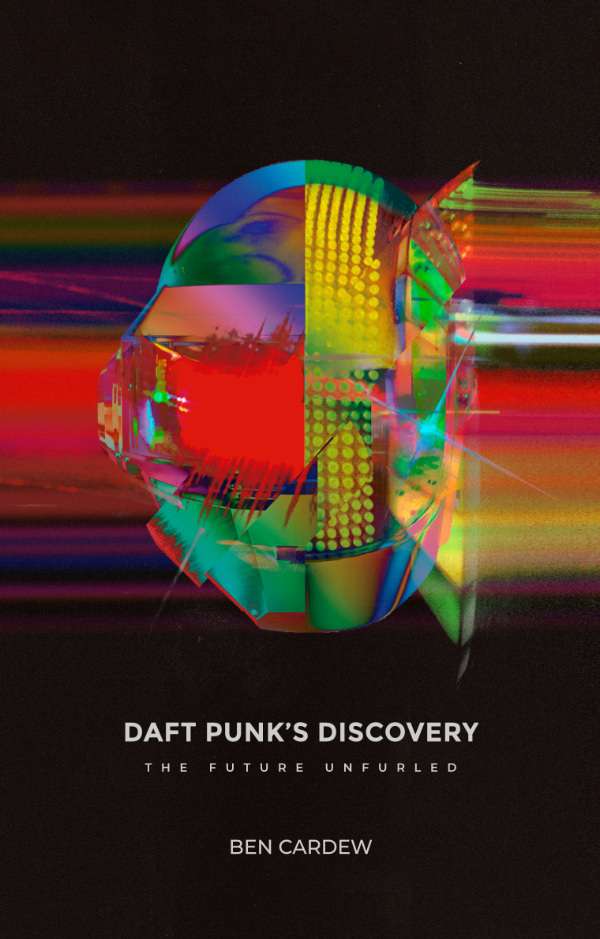

Your EDM Exclusive: The Author of ‘Daft Punk’s Discovery: the Future Unfurled’ Has a Chat and Gives Us an Extract [Velocity Press]

It came as a shock to almost everyone when EDM legends Daft Punk announced their split in February this year. This includes journalist and author Ben Cardew, who was getting ready to publish his in-depth compendium of Daft Punk’s Discovery, a deep dive on the French Duo’s groundbreaking 2001 album. Entitled Daft Punk’s Discovery: the Future Unfurled, the book details quite a bit of Daft Punk’s history, lead-in projects and sound evolution while exploring just how the famous album was made.

Now that we know that 2021 is the end of the Daft Punk era, Daft Punk’s Discovery seems even more important in chronicling what was not only the most important LP in the Daft Punk timeline but one of the most important of all time in EDM. The book is full of lots of heretofore-unknown stories, facts and timeline tidbits about the band: everything from how their helmets happened to why Discovery seemed to endear Daft Punk to American music fans much more than those in their home country of France.

Of particular interest to American fans will be how the duo took so much influence from American music like Chicago house, hip hop and soul. It’s very evident in tracks like their first big hit in Discovery, “One More Time,” where they collaborated with the elusive and well-respected house artist Romanthony, who sadly passed in 2013. The duo’s work with Romanthony on the legendary single that defined their career is the subject of our excerpt, and we were also lucky enough to sit down with Cardew and ask him a few questions about said excerpt, the book and his thoughts on the 21-year timeline of Daft Punk. Q&A is first, excerpt follows.

Aside from their recent breakup, what made you want to write this book?

I actually started writing the book last summer, 2020, and started thinking about it a few years before that. That was pre-break up, obviously, so the split wasn’t a reason that I wanted to write the book. Daft Punk split when I had a draft of the book pretty much done, so I had to do quite a lot of re-writing.

There were a few reasons I wanted to write the book. First, I’ve always loved Daft Punk and Discovery. But I also felt I had something to say about the band and album, having lived through the band’s career and having lived in France. I also interviewed Thomas Bangalter once, around the Human After All era. I love Homework but I don’t think I have enough to say about it to make a book. Whereas there is so much you can look at with Discovery: the Daft Club, Interstella, the robot disguises and – of course – the music itself.

I also felt that Daft Punk were a bit misunderstood. Yes, they are brilliant musicians and changed electronic music. But they were also just two people from Paris. I remember the band’s early days, when they didn’t wear disguises; I remember how people hated “One More Time” when it was released. And a lot of that is forgotten.

Why did you feel it was important to center the book around Discovery? What about that album and period do you think was seminal for the band?

It’s Daft Punk’s best album, for me, and the most influential. It was one of those albums that I remember hearing for the first time and being a little shocked. What the hell is this? What are those metal guitars? And I love albums that do that.

One of the chapters in the book looks at the musical impact of Discovery. And it is everywhere: Autotune, maximalism, electronic stars loving pop music, the rise of soft rock/yacht rock, EDM. Discovery has been called the most influential album of the last 20 years and I totally agree.

Also, you can see a lot of Daft Punk’s career through the prism of Discovery: Homework was the road to Discovery; Human After All was the anti-Discovery; Random Access Memories was the organic Discovery. Basing the book around Discovery gave it a working structure.

There are a lot of great tidbits about Daft Punk prior to Discovery and some facts even after that a lot of fans didn’t know, thus making this book a bit of an expose for many. Do you have a favorite random fact that you discovered while researching the book?

I was fascinated by the idea, which Todd Edwards told me and Tony Gardner also alluded to, that Daft Punk were originally planning to make a live action film around Discovery! I hadn’t heard about that before.

I can’t quite work out how it would fit into the recording of the album – when did they think of it? When did they abandon it? What the hell are space worms? I know we got Interstella but that seems a very different beast. From what Todd says, it seems it was all pretty well planned too – like “Face To Face” was meant to soundtrack a robot battle scene. I would love to know more about that.

Reading the first chapter from which this excerpt came, it seems quite a winding road that led to Discovery. Do you think that was required for Daft Punk to really develop their sound or was it just a condition of where the industry was at the time?

I think it was where Daft Punk were at, at the time. Discovery was a lot of work for them and I think it really drained them – especially Thomas – because it was so ambitious. One of the things I love is that they recorded “One More Time” and “Too Long” with Romanthony, then decided they didn’t want to do a standard house music album, so they had to go back to the drawing board.

It’s also notable that on Discovery Daft Punk were finally able to do a lot of what they had long wanted to do. Like they wanted to work with people like Romathony before Discovery but it didn’t happen. So Discovery was the realization of their dreams, in many ways.

Knowing more possibly than anyone about how Discovery came together save Daft Punk themselves, what’s your opinion on how music is made now versus back then? To summarize: do you think there will ever be another Daft Punk in electronic music, given how music is made now?

Musically, I think there could be. Don’t forget that when Discovery came out, Daft Punk weren’t that far in terms of reputation from, say, Basement Jaxx. And when Human After All came out, a lot of people thought Daft Punk were finished. So this deification of Daft Punk is a relatively recent phenomenon, post the Alive 2006 / 7 tour.

Aside from their changing the game for electronic music (especially in the pop world) with Discovery, what do you think the ultimate legacy is for Daft Punk in general?

This is a vast question! I think Daft Punk showed that you could make massive, mainstream electronic music without compromising your values. They made pop records, sure. But they also made some spectacularly strange songs – I mean, Aerodynamic is so weird, when you think about it – and they became the biggest electronic act in the world! My hope would be, people would go from Daft Punk into some of the bands that inspired them. There is a whole list of them on “Teachers.” Go explore!

Any scoops on next projects for you?

I’m always doing music journalism and making radio and podcasts with Radio Primavera Sound. In terms of book ideas, I have a couple, not entirely unrelated to Daft Punk. But not about Daft Punk either…

The recording of ‘Discovery’ appeared to start in earnest in early 1998 at the duo’s Daft House studio, located in Bangalter’s home and continued for around two and a half years* (FOOTNOTE AT THE BOTTOM OF THE PAGE* Daft Punk have sometimes said that it took them three years to record ‘Discovery.’ It is hard to put an exact time on the album’s recording, given that Short Circuit already existed). The band didn’t quite start from zero, though: elements of “Short Circuit” were already evident in the duo’s live set in 1997. You can hear a brief blast of the song’s distinctive synth stabs right at the start of the Alive 1997 album before “Daftendirekt” enters the fray. Longer live recordings from the time show the song’s basic structure was already in place, minus the circuit meltdown effect that overcomes the track halfway through on ‘Discovery.’

‘Discovery’ seems to have been recorded in two distinct phases, with the two Romanthony collaborations, “One More Time” and “Too Long,” finished early on. Bangalter and De Homem-Christo met Romanthony (aka Anthony Moore) at the 1996 edition of dance music knees-up, the Miami Winter Music Conference, swiftly becoming friends. In 1999 Roulé released Romanthony’s “Hold On,” a gorgeous example of his soulful vocal house that Bangalter licensed from Romanthony’s Black Male Records.

“We wanted to invite him [Romanthony] to sing with us because he makes emotional music,” De Homem-Christo told Remix magazine. “What’s odd is that Romanthony and Todd Edwards are not big in the United States at all. Their music had a big effect on us. The sound of their productions – the compression, the sound of the kick drum and Romanthony’s voice, the emotion and soul – is part of how we sound today.”

“Thomas (Bangalter) knew how to work Roman,” says Glasgow Underground founder Kevin McKay, who worked extensively with Romanthony until the producer died in 2013. “When he turned up, they picked him up at the airport in a limo. They treated him like a star, and he loved it….They are in a really bohemian part of Paris, a really cool studio, one digital room with their samplers, their ASR-10 [sampling keyboard] and all their effects, and a live room with guitars, microphones, the analogue side of things. And he respected them [Daft Punk] in terms of producers, which was hard. He didn’t really respect many people, he was such a snob. They treated him like royalty…. He was in a good place when was recording with them.”

Romanthony was, until his death in May 2013, one of the most enigmatic figures in house music. In a memorial piece, 5Mag spoke of a “strange isolation” around Romanthony, with many of his peers having lost contact with him at the time of his death.

“For the people that don’t know me, it’s OK. I’m not trying to bring people to know me. I am just telling a story, songs that are real to me,” Romanthony explained in a rare interview with Electronic Beats. “My music and production is usually physical pain. When you get a certain rhythm going in the studio, a certain sequence of melodies, sometimes it’s not funny at all. It’s like the opposite of it…. Some of this stuff is on the edge.”

Kevin McKay says that Romanthony “was such an obtuse person at times”. “His view of record releases was that if a record became famous six months or 12 months after it was released and a distributor all of a sudden wanted to get hold of it or make another order because some famous DJ had played it, Romanthony felt that he did not want to supply them at that point because they didn’t believe in the record first time around,” he explains. “His business ethos was really tied up in his ego. It was impossible to separate the two.”

Romanthony, McKay says, would go so far as to make his records sound deliberately weak. “He was guilty of making things sound really bad at mastering. So he would go and get the record mastered, and he would purposefully make it sound worse,” McKay explains. “Why? I don’t know. I did ask him. But he would just laugh and not be straight about it. If I am playing the pop psychologist, then I think that he wanted people to appreciate his art even though it did sound a bit shit. He wanted people to appreciate the songwriting and everything and see-through bad mastering.”

McKay, who has released several Romanthony records on Glasgow Underground, says he was a difficult artist for a label owner. “You really had to handle him with kid gloves,” he says. “But you couldn’t pander to him. Because he’s a smart guy, so he knows when he’s being pandered to, and he’s just like, ‘This is bullshit. I’m out of here.’”

And yet Romanthony was very content with his collaboration with Daft Punk: he admitted, in the interview with Electronic Beats, that the success of One More Time allowed him to step back from making and promoting his own music, with Virgin taking the strain. “That enabled me to just be quiet,” he said.

“The sad thing was, once that record blew up, I think his publisher said, ‘I’ve got over a million dollars for you.’ Or, ‘I am likely to have over a million dollars for you here.’” McKay explains. “And so he just stopped making records. Because he didn’t need to.”

Sure enough, Romanthony wouldn’t work with Daft Punk again. However, a rather ponderous Romanthony Unplugged version of “One More Time” was released via the Daft Club fansite, presumably recorded around the same time as the ‘Discovery’ version.

[embedded content]

In an interview with Pitchfork in 2013, Bangalter claimed that “One More Time” was “mixed and finished and sitting on a shelf” for three years before its release, which would put its recording back to 1997. (Although, confusingly, Pitchfork claims in the same piece that “One More Time” was released in 2001, which isn’t true: the single came out in November 2000.)

Soma Records’ Dave Clarke says that he heard “Too Long,”” the extended R&B / house jam that ends ‘Discovery,’ “at Thomas’s parent’s house way before the rest of the stuff was recorded”, adding that he is pretty sure it was the first song recorded for the album. Whatever the case, completing “One More Time” and “Too Long” seemed to spark a change of direction for the nascent album.

Daft Punk’s Discovery: the Future Unfurled is available for early purchase on Velocity Press’s website and will be released on other platforms September 3.