Say It Loud: 1997 Was A Vintage Year For British Music

What is the greatest year in British music history?

It’s a classic pub question that has been discussed to death, but the usual answers keep getting trotted out – 1967 brought ‘Sgt Peppers’ and ‘Piper At the Gates’; 1969 debuted King Crimson and Led Zeppelin; 1984 was the boiling point of the 80s around the world in the wake of the biggest-selling album of all time. Yet, in the UK (and with mention of some non-British artists for added context), a startlingly great year for music never receives mention – 1997.

An unheard-of pick, for sure. Even if forced to pick from the 90s, most music fans would probably look to 1991’s colossal paradigm shift to grunge. But in all honesty, that was really off the back of one Nirvana record, and searching below the surface will bring only about half a dozen classic LPs. Comparatively, 1997 has a treasury of fantastic music that has shockingly never been compiled before.

If one were to glance at the British charts from this year, it’s obvious that this was far from a perfect ride. A wave of one-hit-wonder fodder swarmed the 12 months: Hanson’s ‘Mmm Bop’ in June; the nonsensical ‘Tubthumping’ by Chumbawamba in August; Aqua’s admittedly well-aged ‘Barbie Girl’ (which was basically PC Music before PC Music); all capped off with a Christmas Number One race featuring the Teletubbies. I promise it gets far better.

– – –

[embedded content]

– – –

Big Beat’s Big Peak

A year that begins with the release of Daft Punk’s debut album is already christened a classic, but in 1997, British dance music reached an apex with the explosion of big beat.

Known for its standout artists Fatboy Slim, The Chemical Brothers and The Prodigy, big beat was a subgenre of electronica that crossed rave music with breakbeats and the ever-so-slight treacle of rock sensibilities. In short, it was electronic music for the NME crowd, evidenced by The Chemical Brothers’ famous collabs with Noel Gallagher and Richard Ashcroft. Going against the faceless, reclusive personas of most electronic artists, big beat artists had the bold personality of rock musicians that commanded attention from mainstream music outlets of the time. As a result, big beat became one of the few instances of electronic music at the forefront of British culture, rippling for a few precious years where Keith Flint and Fatboy Slim became cultural icons.

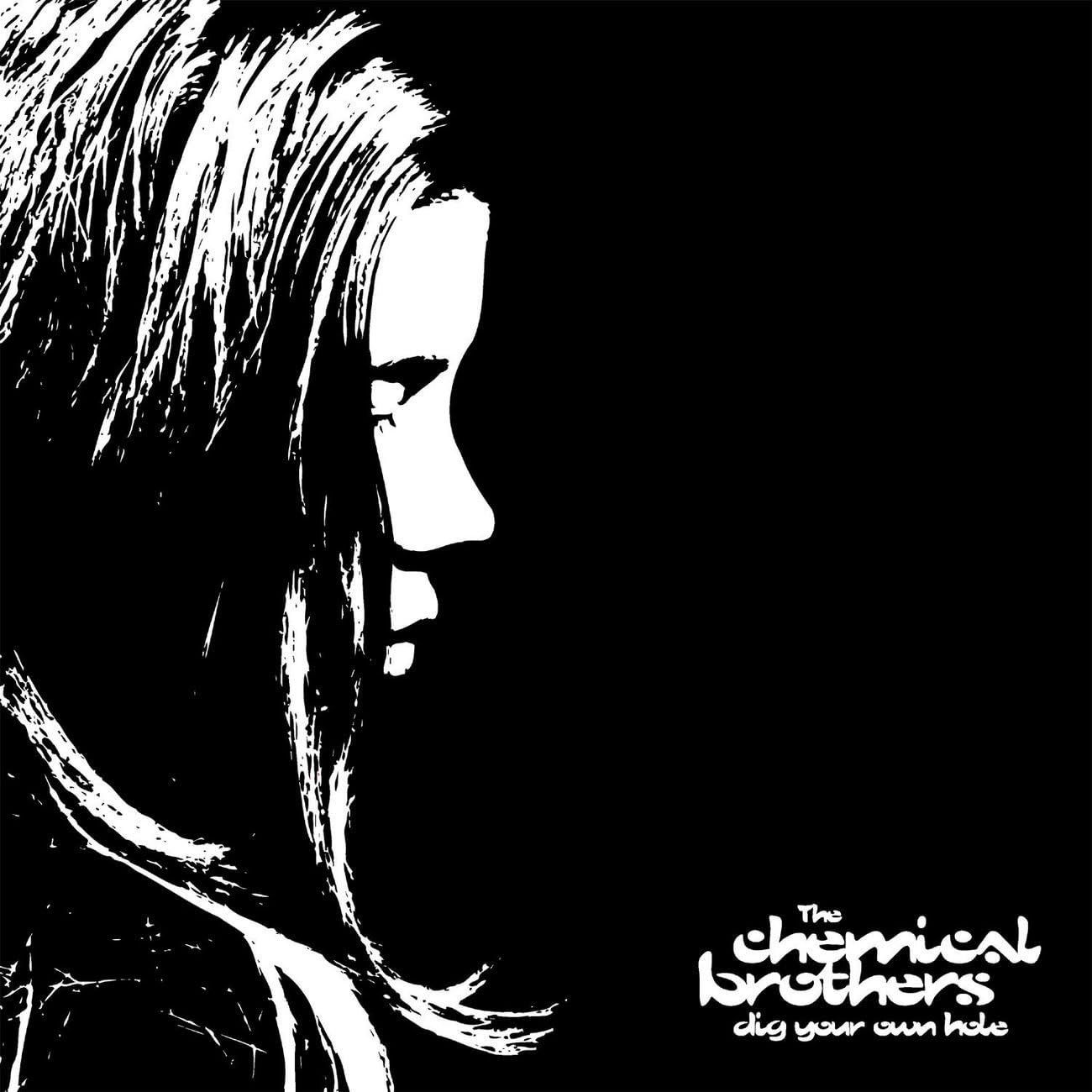

Two big beat records would define 1997, and the 90s in general.

Building from their solid debut record, The Chemical Brothers’ ‘Dig Your Own Hole’ is the perfect example of big beat’s chameleonism. Their second effort packs a record store’s worth of sounds into a set of high-intensity breakbeats that run on plutonium and sweat. Psychedelic rock had never been so overtly prominent in electronic music before, but the duo managed to utilise the head-dilating power of psychedelia to further intensify the rush. Chief among the examples of this is the blaring ‘Setting Sun’, one of two UK number one singles the album produced that brought a uniquely heady combination of styles not heard on the radio before.

Meanwhile, The Prodigy delivered a special kind of heresy to big beat. Their 1997 album ‘The Fat Of The Land’ was equally as in-the-red and rave-ready as The Chemical Brothers. However, the album marked the first proper introduction to the band’s in-your-face image spearheaded by Keith Flint, who was the idealisation of a hell-raising punk singer fully realised.

The group had the foes to back it up, too. ‘The Fat Of The Land’ launched controversy into controversy as they were banned from the BBC upon the release of ‘Firestarter’ and discussed in the House of Parliament about the techno hand grenade that was ‘Smack My Bitch Up’. But the cages The Prodigy rattled – along with the buzz The Chemical Brothers generated – in 1997 would have an indelible impact on British culture, even as big beat fell by the wayside by 2000.

[embedded content]

The Curious Case of David Bowie’s ‘Earthling’

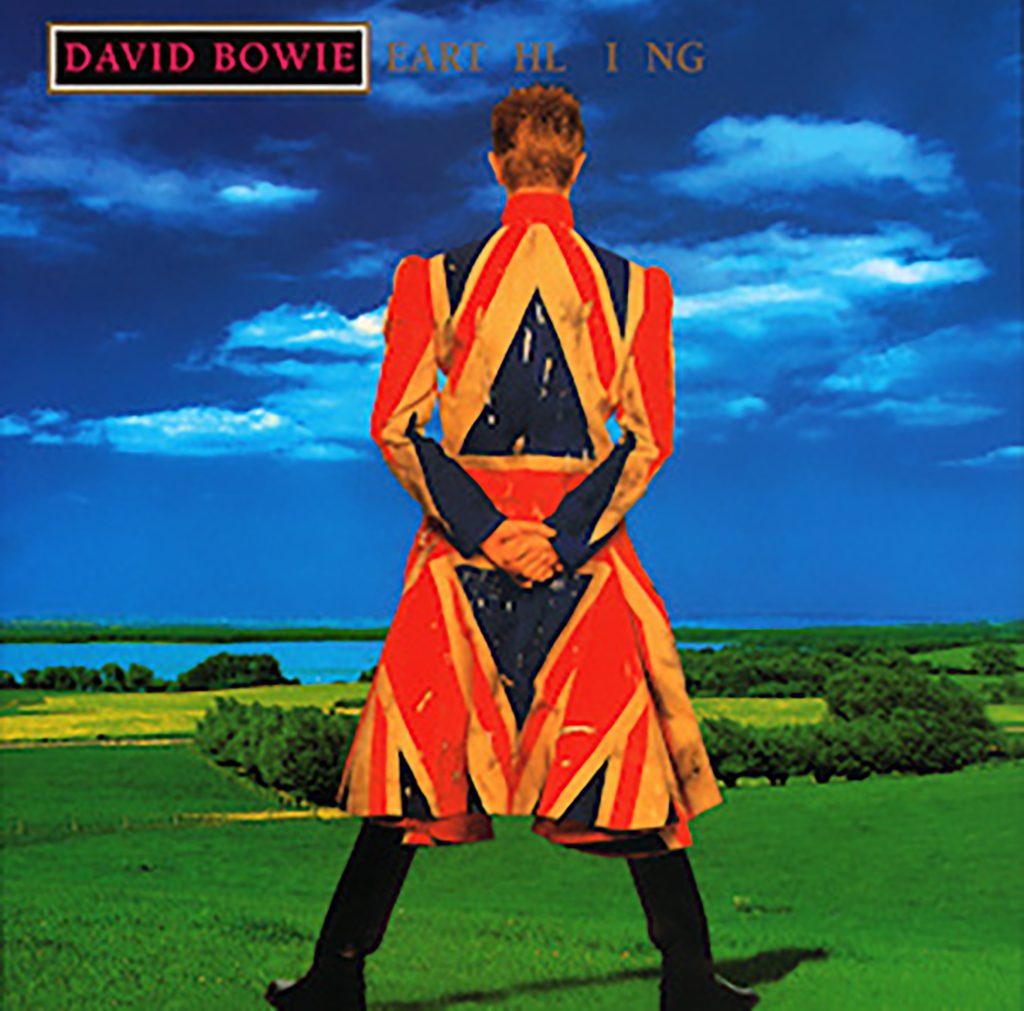

Rave culture was Britain’s defining new scene in the 1990s, and towards the end of the decade, popular music’s elite class took a keen interest in what was going on in these circles. Kylie Minogue’s ‘Impossible Princess’ heavily borrowed from trip-hop and jungle, and in 1998, Madonna would make the rave-pop crossover to end all rave-pop crossovers with ‘Ray Of Light’. But in 1997, David Bowie released ‘Earthling’, a weird little record that saw Bowie creating art rock songs out of the sounds of jungle and electronica.

Of course, hearing Bowie making a jungle album was enough to have it written off by almost everyone at the time, but he shows a demonstrable excitement in merging these worlds. There’s a strange, kitschy appeal to what he did on his 21st LP, particularly in his freakish performances and electronics that all earnestly mimic what the 90s thought was futuristic (cue UFO sounds!). Even still, ‘Earthling’ assembles high-quality production that could be mistaken for collaborations with Goldie and The Chemical Brothers, and the record radiates with Bowie’s belief in the potential of the genres he was excavating.

The jungle and art rock crossover did not catch on, but Earthling stands as a valiant effort that, when viewed in a bigger picture, showed the hidden partnership that could exist between underground electronic music and pop ‘n’ rock. After all, Björk had been finding its untapped potential for years, and brought it to a climax with her masterpiece ‘Homogenic’ in 1997.

[embedded content]

Electronic Music’s New Directions

Speaking of underground electronic music, that too was in a state of flux in 1997. With trip-hop, jungle and IDM music arriving earlier in the decade, the year caught these genres in a pivot, with its key artists diverting into nuanced avenues to progress the sounds beyond their first iterations.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-84882-1450911515-4418.jpeg.jpg)

Portishead’s self-titled follow-up to ‘Dummy’ featured more wicked suspense and a film-noir aesthetic over their familiar trip-hop formula. Drill & bass saw a widening of scope with releases from Aphex Twin and his explosive and emotive ‘Come To Daddy’ EP, as well as Squarepusher’s more insular and frenetic record ‘Hard Normal Daddy’ (was there a daddy obsession this year?). Autechre began to go down their claustrophobic IDM rabbit hole with ‘Chiastic Slide’, and projects from Photek and Roni Size & Reprazent gave breakbeat an import of jazz elements in a subgenre known as ‘jazzstep’.

Electronic music was pushed outward, pulled into the future, and came out the other side of the year with a fresh set of possibilities.

[embedded content]

‘Be Here Now’ and the Death of Britpop

Britpop was a genre with limited potential, huge success and a weird aura of nationalism surrounding it. Despite the individual politics of Britpop bands during their heyday, the genre itself was rooted in a blind nostalgia for the British pop-rock music of the 60s. Nothing inherently wrong with a revival, but as bands like Oasis, Blur and Suede achieved success, they became tools to market Britain itself. Oasis was never too far away from a British flag at gigs or in press photos, and Blur’s most iconic single illustrated a subset of British life spoken with an unmistakably territorial accent. These band leaders became icons for a growing nationalist ‘lad culture’ that gave people credence to become feverishly jingoistic, wishing for the “good old days” that were only good if you were an S.W.M.: Straight White Male™.

Then 1997 came. Oasis were tasked with following up their commercial behemoth ‘(What’s The Story) Morning Glory?’, and had uninhibited grounds to exercise their artist licence. The result was a project of seismic proportions, stretching 70 minutes and having pre-release secrecy on the level of an SAS mission. In the summer of ‘97, ‘Be Here Now’ was released, an album that encapsulated all the limitations of Britpop in one handy, recyclable package.

Oasis went into the recording of ‘Be Here Now’ with a child’s idea of ambition. With the philosophy “more = better” at the helm, the band managed to create such overblown mixes that an hour-plus of listening can strain the ears. Strings, horns, slide whistle and Johnny Depp’s slide guitar clutter the thick hedge of guitars that already feel like stepping through an overgrown lawn. Moreover, every hook and riff is lifeless out-of-the-box, with lyrics that were likely smeared hurriedly onto coke mirrors in desperate bids at sloganeering. None of these songs are “about” anything, just vapid attempts at bringing the masses together.

‘Be Here Now’ is the intersection where copious amounts of money and drugs and complete creative control meets a limited creative capacity. Nothing Oasis do is boundary-pushing other than the obscene runtimes of some of these songs. However, could they be expected to? As iconic as their previous stuff may be, when they had made a career off of the ideas of the Beatles, Kinks, and Who, what could they do when they decided to be ambitious? They simply exposed why Britpop had to die, why there was nowhere for it to go beyond staring at the past and wishing to live in that world again. After the summer of ‘97, Britpop lost the nation’s full attention and moved on. As a genre that was furthering the amount of braindead nationalism in the UK, it’s an upside to be able to hear the moment when the bubble burst.

[embedded content]

Mogwai and the Rebirth of Post-Rock

Post-rock is an exploratory and abstract form of rock that pays more attention to atmosphere and texture than lyrics and verse-chorus structures. The term ‘post-rock’ was originally thrown onto cult UK group Bark Pyschosis’ 1994 album Hex, and in the latter half of the 90s a new generation picked up the spark laid down by bands like them and Slint. With multinational representation, post-rock was assimilating into its golden age in 1997, with releases from Labradford in the USA, the distinguished Godspeed You! Black Emperor in Canada, and the humble beginnings of an Icelandic band called Sigur Rós.

Mogwai’s ‘Young Team’ was the UK’s marquee contribution to the rebirth of this style, known for its moments of vigorous noise-rock. At their peak, the guitars on ‘Young Team’ had a burning distortion that roared past their post-rock predecessors. However, it’s the quieter, tender moments of drifting guitar passages that are more often found in succeeding UK music inspired by ‘Young Team’. The jangly reverb-soaked guitars would also be used by Radiohead, early Coldplay and their alt-rock contemporaries. In a canonic sense, Mogwai’s 1997 debut placed them as one of the premier bands in pushing the cataclysmic scale of instrumental rock.

[embedded content]

OK Computer

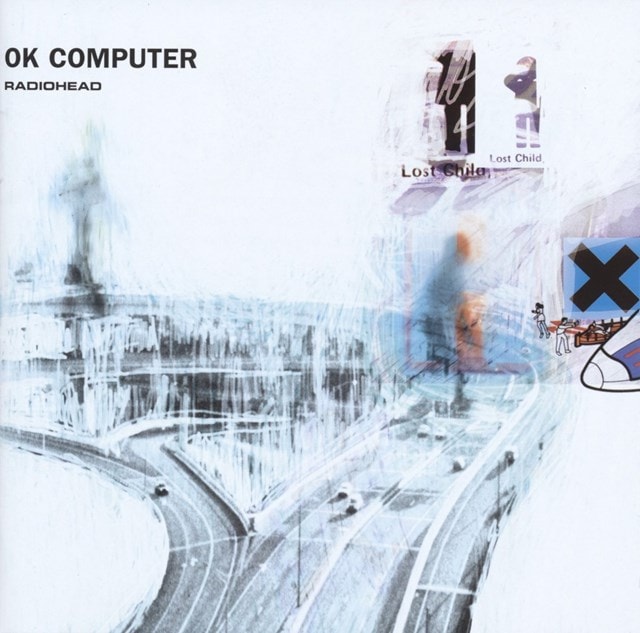

What new revelation can be said about ‘OK Computer’? Radiohead’s opera to the isolation of a growing hyper-consumerist, hyper-technological world is the glistening peak of a spectacular year for British music. But what’s so fascinating is how the band’s third album perfectly culminates everything great about 1997.

‘OK Computer’ marked the advancement of British rock music past Britpop, one that was cleverly critical of the UK government and its gross use of nationalism to justify actions against our interests. Tracks like jangly ‘Let Down’ and the distorted guitars on ‘Exit Music’ mirror what post-rock was pushing for. The breakbeats used on ‘Airbag’, trip-hop layout of ‘Climbing Up The Walls’ and general digital filter over the album incorporates the electronic music of the year, catching on far sooner than David Bowie did. Finally, nothing here is as danceable as big beat, but the provocative commentary on Blair’s government and modern society compliments the rebellious antics of The Prodigy, and the way ‘Dig Your Own Hole’ refracts the sounds of the past through a futuristic lens is similar to ‘OK Computer’.

The general sound of the classic music from 1997 feels connected – it’s got a certain grit, cold sheen and patina. This is not to mention the other daring art rock that came in 1997, such as Spiritualized’s ‘Ladies And Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space’ and Stereolab’s ‘Dots & Loops’. The key albums of the year were musically progressive, looking toward an idealised version of the future where genres cross over in wild and confounding ways, which prepared us for how music would advance in the internet age. ‘OK Computer’, with all its influence and pedigree, bundled all of that into one.

– – –

[embedded content]

– – –

Words: Nathan Evans // @nayfun_evans

– – –